Oct 26, 2018

On Monday, October 29th stroke support organisations from around the world will create a global moment to demonstrate that there is life after stroke – that a stroke may bring you down but that it’s possible to get #UpAgainAfterStroke.

It is estimated that there are around 80 million stroke survivors around the world each one facing many challenges of daily living after having had a stroke. Stroke survivors face many obstacles and the scale of this is dependent on where they live, their socioeconomic status and the severity of their stroke.

Despite these obstacles on World Stroke Day 2018 we want to focus the world’s attention on what unites stroke survivors and caregivers – their resilience, their capacity to build on the things that stroke can’t take away and their determination to keep going on their journey of recovery.

For every stroke survivor, Getting Up Again After Stroke takes commitment. Building support networks with other stroke survivors, sharing stories of survival and recovery can help people stay hopeful and focused on progressing.

For every stroke survivor, Getting Up Again After Stroke takes commitment. Building support networks with other stroke survivors, sharing stories of survival and recovery can help people stay hopeful and focused on progressing.

At the same time, caring for someone who has had a stroke can be demanding and many of the relationships that bind us change. It is understandable that carers need help too.

Policy-makers need to understand that long term commitment and attention to the needs and rights of stroke survivors and their caregivers will contribute to better health and wellbeing, outcomes, increase independence and reduce demand on healthcare, social and welfare systems.

SAFE member organisations from 30 European countries are preparing a series of events to mark World Stroke Day this year, under an overarching theme #UpAgainAfterStroke.

Find your country’s organisation HERE and help us raise stroke awareness for this World Stroke Day.

Stroke Alliance for Europe with all our members from 30 European countries, proudly stands with the stroke survivors and their families on October 29th, World Stroke Day.

Oct 24, 2018

The slogan and hashtag of this year’s World Stroke Day is #UpAgainAfterStroke. The SAFE member organisation from Serbia sent us a very inspirational story of a young woman who managed to conquer stroke and kept pursuing her dreams.

Photo: Private archive of Marina Krsmanovic

Marina Krsmanovic from Serbia, a nursery teacher and mother of two, never was a smoker and did sports on regular basis. Despite her healthy lifestyle, in December 2017 she felt that her right arm was paralysed, she lost her sight and she noticed speech difficulties.

She did not wait and she immediately called for help. Within one hour she was admitted to St. Sava (Sveti Sava) Special Hospital for cerebrovascular diseases in Belgrade, Serbia. The medics diagnosed a stroke which was a consequence of a congenital heart disease. She was sent to the Institute of Cardiovascular diseases where she had a heart surgery on 24th January 2018.

She found her motivation and strength for recovery in her children. She adopted a new diet, changed the way of thinking and she now says that she has started enjoying her life, finding happiness in small things and that she always has positive thoughts. It’s safe to say that her fast reaction at the first symptoms, quick transportation to hospital and of course high quality treatment in the above mentioned medical institutions were the key for her successful recovery. Now, she can function independently, she has returned to her workplace…

When we got in touch with her, we heard some great news and it’s not enough to say that we were amazed. Apart from returning to her everyday routine, Marina has returned to her hobby that she practiced before stroke- downhill mountain biking. She even won a medal at a competition that took place on Zlatibor mountain (Western Serbia) at which she was the only female competitor!

Photo: Private archive

She said that her only goal has been to take part in the competition and to prove it to herself that she could tame the mountain once again. Taking part in the competition is worth all the attention and admiration one could get but winning a medal is like reaching the top of the world.

Photo: Private archive

Her message to all of us is stick to positive thinking, enjoy little things and enjoy your life to the fullest. We hope that Marina’s story will motivate people never to give up and to keep fighting. We, on our behalf, have a duty to do everything we can to make life easier for those who had suffered a stroke, to help them get #UpAgainAfterStroke!

If you want to share your experiences with SAFE and if you want set an example for people who are facing a stroke and all its consequences, please contact us via Facebook and Twitter.

Oct 21, 2018

At this year’s World Stroke Congress In Montreal, Canada, SAFE was present through a variety of activities, from chairing stroke support sessions, being one of the key speakers and presenters, having a very well noticed and visited information stand, to actively participating in the World Stroke Day workshop and shaping the World Stroke Campaign in the years to come.

SAFE President Jon Barrick presented the SSOFT project, an online ‘how to’ toolkit for a range of advocating skills training, from setting up a stroke support organisation to leading PR and advocacy campaigns. This tool aims to build capacity of the European SSOs but can be used much broader to increase one world voice for stroke. His presentation sparked interest even among SSOs from other continents leading to an interesting exchange of ideas and suggestions for its further development. The SSOFT project will be completed by end of November 2018. Project team are looking at the future development such as translation into other languages, additional modules, global scope, said Barrick, but it is depending on funding. The presentation was broadcasted live on Facebook and the video can be found here.

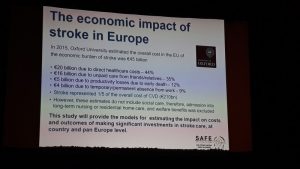

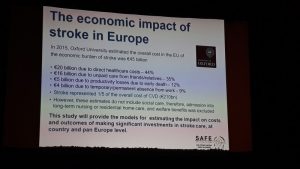

In addition to the SSOFT project, SAFE had a chance to present the economic Burden of Stroke Report, scheduled to be published towards the end of 2019, as well as the SAFE & Industry Partner collaboration project on Life With Spasticity.

However, the Stroke Action Plan for Europe 2018-2030, a joint SAFE and ESO project got the majority of attention due to the fact that it just has been launched in May this year and is aimed to set the road map for stroke prevention, treatment and life after stroke in Europe in the next 12 years.

However, the Stroke Action Plan for Europe 2018-2030, a joint SAFE and ESO project got the majority of attention due to the fact that it just has been launched in May this year and is aimed to set the road map for stroke prevention, treatment and life after stroke in Europe in the next 12 years.

Successful examples and case studies from around the world, such as the one of the Swedish Stroke Registry and their latest project about caregivers and how they are coping with the consequences of strokes in their loved ones. The need for comprehensive and systematic follow up reviews for stroke survivors, after 3, 6 and 12 months was particularly stressed out.

Prof. Bo Norrving

We heard from Prof. Bo Norrving, University of Lund, Sweden, that one of 6 strokes was eradicated in Sweden over the last 6 years, meaning 14,000 in absolute number of strokes, and saving one billion euros. The reason for this success lays in treatment of TIA, atrial fibrillation and use of preventive medications. Stroke is probably the single most preventable disease of all. It may be that I am wrong, but I would like to be proven to be wrong, said Prof. Norrving.

During a separate open session on stroke as part of the non-communicable disease, Stephanie Mohl on behalf of American Heart and Stroke Association opened the conversation saying: Here we are in 2018 and we still need to talk about why patients need to in center of the healthcare, pointing towards all of the necessary efforts to convince the policy decision makers to listen to the patient voice in almost all parts of the world.

The way non-communicable diseases were addressed so far by the policy makers, the NCD acronym might as well stand for No Can Do, said Jon Barrick. This needs to be changed, but we need to be aware that people don’t put energy into hopeless campaigns, so stroke support organisations should be more active in showing perspectives and opportunities for stroke survivors and their carers.

SAFE was active on social media during the whole three days of the World Stroke Congress. For more information, please visit our social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter.

An open session on stroke and non-communicable diseases

Oct 14, 2018

The story first appeared on ScienceDaily.com

New findings suggest that diet is a major contributor for the increased risk of hypertension in black compared to white Americans. The results, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, are part of the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, which looks at the incidence of stroke in approximately 30,000 individuals. The study is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), a part of the National Institutes of Health.

“This study addresses a lead cause of racial disparity in mortality and identifies potential lifestyle changes that could reduce racial disparities in both stroke and heart disease,” said Claudia Moy, Ph.D., NINDS program director and one of the study authors.

In the study, led by George Howard, Dr.P.H., a biostatistics professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, researchers studied individuals over the age of 45 over a period of 10 years and looked to identify risk factors associated with the higher likelihood of developing high blood pressure in the study participants.

“The majority of disparities we see in the health of black versus white Americans are cardiovascular in nature,” said Dr. Howard, “and of these, all are tied to an increase in high blood pressure.”

For both men and women, a diet composed of high amounts of fried and processed foods and sweetened beverages was the greatest factor associated with why blacks are at a greater risk of developing high blood pressure compared to whites. For both men and women, other important factors included salt intake and education level. For women, additional factors contributing to the racial difference in high blood pressure included obesity and waist size.

“One of the main factors affecting the difference between the black and white population is cardiovascular disease, and the increased risk of high blood pressure among black Americans could help explain why their life expectancy is four years shorter than that of whites,” said Dr. Howard. “Understanding how we can prevent this increased risk of hypertension in blacks is critical for reducing health disparities among the black population.”

The researchers hope that these findings could be applied to reduce the prevalence of hypertension and thus the risk of stroke and heart attack in the black American population. This study suggests that lifestyle changes, particularly changes in diet, could help reduce the disparities seen in black versus white Americans.

“The best way to treat high blood pressure is to prevent it from occurring in the first place,” said Dr. Howard.

The REGARDS study includes more than 30,000 black and white Americans, approximately half of whom live in the Stroke Belt, an area in the southeastern United States where the rate of stroke mortality is higher than the rest of the country. Of these, 6,897 participants, 1,807 black and 5,090 white, were analyzed for this study.

In 2016, the NINDS launched a stroke prevention campaign called Mind Your Risks, which is designed to educate people aged 45-65 about the link between uncontrolled high blood pressure and the risk of having a stroke or developing dementia later in life.

Story Source: NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. “Diet rich in fried and processed foods linked to increased hypertension in black Americans: Study suggests a change in diet could mitigate increased risk for stroke.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 3 October 2018. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/10/181003193936.htm>.

Oct 5, 2018

As World Stroke Day 2018 approaches, we would like to invite you to register your event on the World Stroke Campaign website, by clicking on this button below.

Registration link WSD 2018

SAFE is proud of our member organisations who did tremendous work around World Stroke Day 2017, wholeheartedly supporting the “What’s your reason?” campaign. through use of texts, visuals and other material produced by WSO for this purpose.

We also used the opportunity to convey our own messages based on the Burden of Stroke in Europe Report findings, related to the lack of prevention and stroke awareness campaigns in Europe, as well as the underestimated danger coming from the three biggest stroke risk factors- blood pressure, AF and high cholesterol.

Whether it was a series of lectures like in Cyprus, Portugal, or a book promotion in Luxembourg or sports events that our colleagues from Ireland, Poland and many other countries organised- we showed that raising awareness of stroke was an important topic. Many of our organisations start the preparation for the World Stroke Day long before 29th October. For example, our colleagues from Slovenia started with activities dedicated to WSD as early as September by attending the Festival for the third age and with September’s national gathering, having a stand and giving a free lecture on how to beat stroke, delivered by the vice-president of the Slovenian Stroke Support Organisation, dr. Tatjana Erjavec.

What is your plan for this year? Register your event, put yourself on a map of stroke activists from around the world.

For every stroke survivor, Getting Up Again After Stroke takes commitment. Building support networks with other stroke survivors, sharing stories of survival and recovery can help people stay hopeful and focused on progressing.

For every stroke survivor, Getting Up Again After Stroke takes commitment. Building support networks with other stroke survivors, sharing stories of survival and recovery can help people stay hopeful and focused on progressing.

However, the Stroke Action Plan for Europe 2018-2030, a joint SAFE and ESO project got the majority of attention due to the fact that it just has been launched in May this year and is aimed to set the road map for stroke prevention, treatment and life after stroke in Europe in the next 12 years.

However, the Stroke Action Plan for Europe 2018-2030, a joint SAFE and ESO project got the majority of attention due to the fact that it just has been launched in May this year and is aimed to set the road map for stroke prevention, treatment and life after stroke in Europe in the next 12 years.